Making Music In A Time Of War

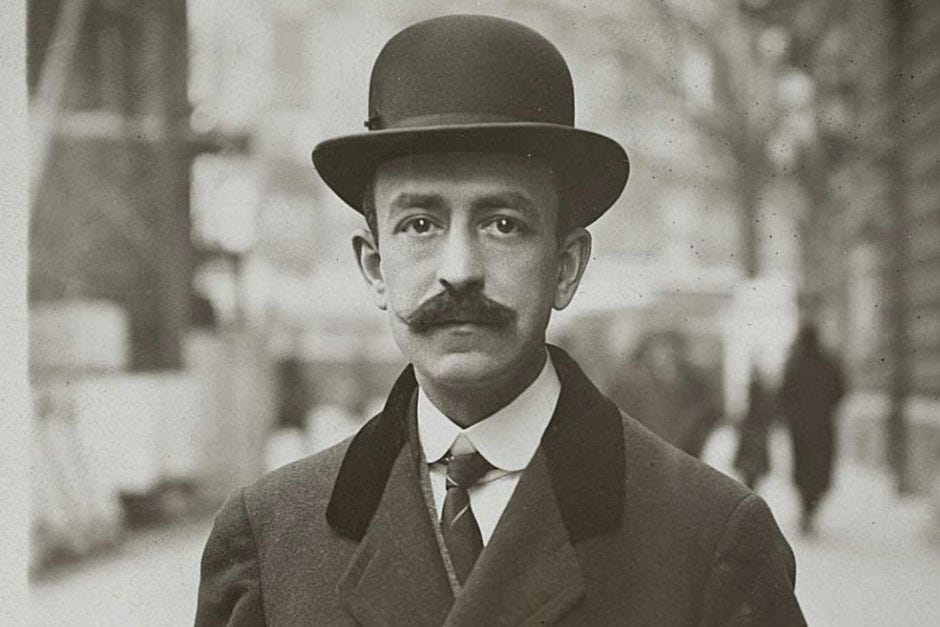

Manuel de Falla (1876-1946)

Reflections on "Sacred Passions: The Life and Music of Manuel de Falla" by Carol A. Hess.

We can learn from eras that provided ideal conditions for art - generous patrons, leisure, national confidence, and cultural vitality. But what about the naturally talented artist who is born at a less fortunate time, one of national decline, civil war, growing uncertainty, fear, and scarcity? The Spanish composer Manuel de Falla is such a figure.

By the time Falla was born, the peak of Spanish global power and its Golden Age of culture had long passed and Spain's loss in the Spanish-American War was the end of its status as a major world power. Then there was WWI and the Spanish Civil War, and he died just one year after the end of WWII, so war was thundering in the background of his entire creative life. If murder is everywhere, and it seems as though the world is ending, why make music at all?

He was born in Cádiz, the ancient port city with Phoenician heritage. He established his own literary magazines at age 12, and his admiration for Christopher Columbus was a recurring theme. His mother taught him piano and nurtured his love of music, taking him to recitals and concerts. He went on to study piano at Madrid's Escuela Nacional de Música y Declamación, which was established in 1830 under the patronage of María Cristina, Queen Consort of Ferdinand VII of Spain, and it was heavily influenced by Italian musical traditions.

Carol A. Hess described him as a “sin-haunted composer” in her biography Sacred Passions: The Life and Music of Manuel de Falla. “Deeply religious and distrustful of wealth, Falla led a life of quietude and abnegation,” she wrote, “He lived as a monk-like ascetic yet wrote some highly sensual music.” Stravinsky described Falla as “modest and withdrawn as an oyster” when he met him in Paris. Based on the evidence Hess draws upon, the same temperamental sensitivity and spiritual nature that made him capable of such beautiful creations also made the violent and nationally divisive times he lived through very torturous for him.

The period did have many writers and world-famous painters like Dali and Picasso, but cumbersome patronage-dependent forms like concert music and opera were harder to sustain. While he started life in relative bourgeois comfort, his father’s businesses failed and he had to become the family breadwinner at the very beginning of his career, leaving little time for composing. Falla struggled financially throughout his career, barely scraping by from teaching and a few brief periods of limited patronage.

The aftermath of the Spanish-American War in 1898 brought about a renewed focus on national identity among his generation of writers and artists during this “Silver Age.” Falla tried to put the national spirit into music.

He seems to have experienced the pain of unrequited love or an otherwise unsuccessful engagement with Maria Prieto Ledesma and remained a bachelor after that.

In 1907, Falla went to Paris, where he lived in modest conditions, earning a living as a piano teacher and with a touring pantomime company.

Hess describes all of this pieces in detail but here are a few highlights:

La vida breve (The Short Life) premiered in Nice in 1913, blending Spanish folk and classical styles.

Noches en los jardines de España (Nights in the Gardens of Spain) was a symphonic suite for piano and orchestra, which showcases his period of impressionistic style, evocative of Spanish landscapes. If you only watch one of these videos (the best I could find for free) let it be this one:

The song cycle Seven Folksongs composed by Falla in 1914 draws inspiration from Spanish folk melodies: "El paño moruno" (The Moorish Cloth) "Seguidilla murciana" (Murcian Seguidilla) "Asturiana" (Asturian Song) "Jota" (Jota) "Nana" (Lullaby) "Canción" (Song) "Polo" (Andalusian Gypsy Song)

During his time in the music scene of Paris his creativity thrived. Hess describes this as a really exciting time for Falla, as he worked with and met many of the greatest composers of the era. But the onset of World War I compelled him to return to Spain halting his prospects there.

In 1915 he presented El Amor Brujo (Love, the Magician) - an opera infused with flamenco and Andalusian folk culture. It features a famous segment “Ritual Fire Dance" and tells a story of romantic jealousy with elements of the supernatural.

El sombrero de tres picos (The Three-Cornered Hat), was a ballet choreographed to Falla’s music and based on a novella by Pedro Antonio de Alarcón which premiered at Alhambra Theatre, in London along with Picasso’s designs. Despite receiving acclaim for this performance, his grief over his mother’s death at the time overshadowed any joy from the success of the show.

Falla continued to explore national identity themes, organizing a competition for cante jondo singers to preserve this authentic folk style, as well as the puppet tradition in El Retablo de Maese Pedro (Master Peter's Puppet Show), a puppet opera based on an episode from Cervantes' Don Quixote.

Tortured with poor health, Falla became more ascetic in his home in Granada, where his sister looked after him. In the Hess biography, a student recalls walking in to find him speaking to the bugs on the floor with a slipper in hand, assuring them they were all God’s creatures, but they had to go.

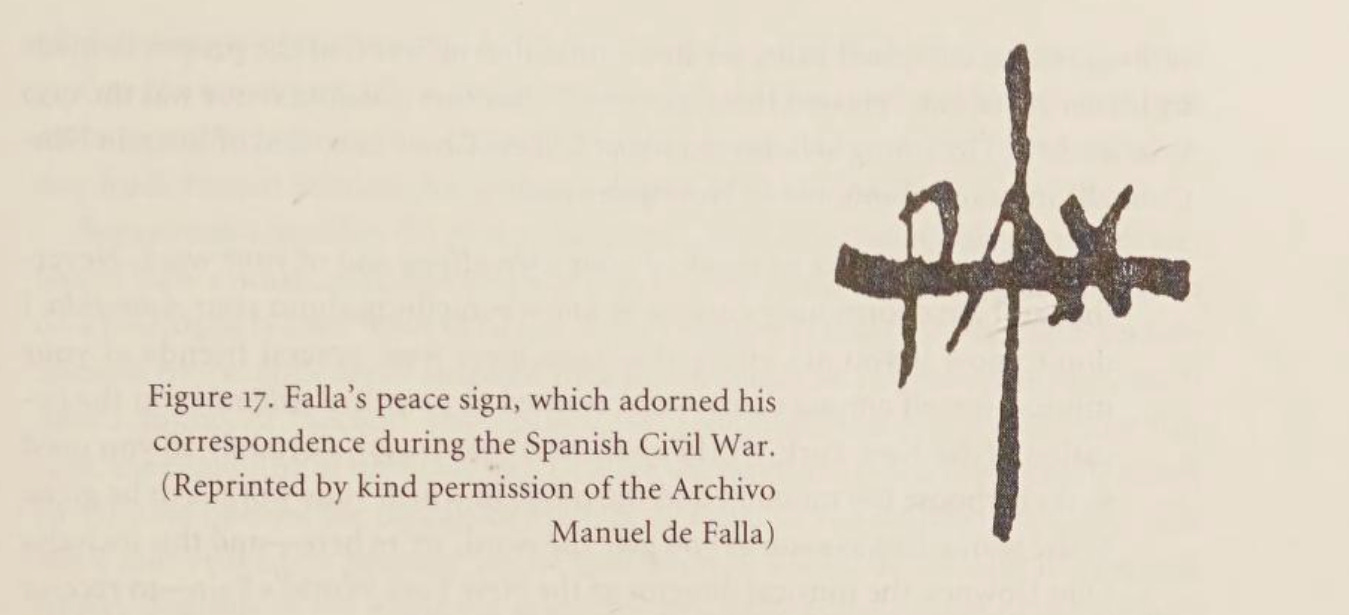

As political tensions escalated in Spain, he found himself at odds with the direction of things. He had been a political liberal by the standards of the time and was supportive of land reform and workers' rights, but he became disillusioned by the church burnings and the desecration of Spain's Catholic identity. He lost friends in the civil war, and he became more sympathetic to Franco’s nationalists after witnessing the anticlericalist violence. All of the violent reprisals deeply troubled him, exacerbating his anxiety and bad health, as his feet, his eyes, his lungs were all failing. Despite being celebrated by the nationalist press and government, he became increasingly withdrawn, indecisive, and evasive on political matters.

In 1938, Falla was appointed president of the Instituto de España by government decree, but he ultimately chose to escape to Argentina in 1940, invited by the Institución Cultural Española of Buenos Aires.

There he tried to work on L’Atlántida, a choral symphony and monumental composition based on the legend of Atlantis (involving Christopher Columbus). It was inspired by the Catalan poem by Jacint Verdaguer. Others worked on the unfinished piece after his death, and in 1961, it was finally performed in Barcelona.

In 1946, he passed away in his sleep from heart failure.

In his final years he wrote in a letter, “When I’m working at my craft, many times I ask myself to what end I do it. But in the end: God above everything, and always going forward as if we were in the best of all worlds! Besides, there’s always the hope that one of these days they’ll invent a way to travel to another planet, although when we arrive, perhaps we won’t be admitted.”

A very engaging piece about an very interesting composer, artist Manuel de Falla. Usually I don´t listen to this style of music much but I liked, was moved by the samples of his work you provided. A very creative man whose life story is intriguing. He doesn´t seem to have had much exposure outside Spain.